Hierarchical models

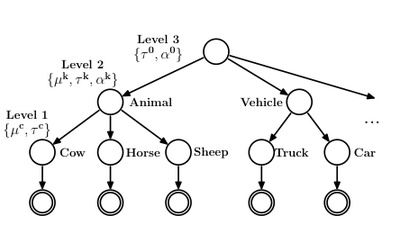

Human knowledge is organized hierarchically into levels of abstraction. For instance, the most common or basic-level categories (e.g. dog, car) can be thought of as abstractions across individuals, or more often across subordinate categories (e.g., poodle, Dalmatian, Labrador, and so on). Multiple basic-level categories in turn can be organized under superordinate categories: e.g., dog, cat, horse are all animals; car, truck, bus are all vehicles. Some of the deepest questions of cognitive development are: How does abstract knowledge influence learning of specific knowledge? How can abstract knowledge be learned? In this section we will see how such hierarchical knowledge can be modeled with hierarchical generative models: generative models with uncertainty at several levels, where lower levels depend on choices at higher levels.

Learning a Shared Prototype: Abstraction at the Basic Level

Hierarchical models allow us to capture the shared latent structure underlying observations of multiple related concepts, processes, or systems – to abstract out the elements in common to the different sub-concepts, and to filter away uninteresting or irrelevant differences. Perhaps the most familiar example of this problem occurs in learning about categories. Consider a child learning about a basic-level kind, such as dog or car. Each of these kinds has a prototype or set of characteristic features, and our question here is simply how that prototype is acquired.

The task is challenging because real-world categories are not homogeneous. A basic-level category like dog or car actually spans many different subtypes: e.g., poodle, Dalmatian, Labrador, and such, or sedan, coupe, convertible, wagon, and so on. The child observes examples of these sub-kinds or subordinate-level categories: a few poodles, one Dalmatian, three Labradors, etc. From this data she must infer what it means to be a dog in general, in addition to what each of these different kinds of dog is like. Knowledge about the prototype level includes understanding what it means to be a prototypical dog and what it means to be non-prototypical, but still a dog. This will involve understanding that dogs come in different breeds which share features between them, but also differ systematically as well.

As a simplification of this situation consider the following generative process. We will draw marbles out of several different bags. There are five marble colors. Each bag contains a certain mixture of colors. This generative process is represented in the following WebPPL example (for a refresher on the Dirichlet distribution, see the Appendix).

var colors = ['black', 'blue', 'green', 'orange', 'red'];

var makeBag = mem(function(bagName){

var colorProbs = dirichlet(ones([colors.length, 1]))

return Categorical({vs: colors, ps: colorProbs})

})

viz(repeat(100, function(){sample(makeBag('bagA'))}))

viz(repeat(100, function(){sample(makeBag('bagA'))}))

viz(repeat(100, function(){sample(makeBag('bagA'))}))

viz(repeat(100, function(){sample(makeBag('bagB'))}))

As this examples shows, mem is particularly useful when writing hierarchical models because it allows us to associate arbitrary random draws with categories across entire runs of the program. In this case it allows us to associate a particular mixture of marble colors with each bag. The mixture is drawn once, and then remains the same thereafter for that bag. Intuitively, you can see how each sample is sufficient to learn a lot about what that bag is like; there is typically a fair amount of similarity between the empirical color distributions in each of the four samples from bagA. In contrast, you should see a different distribution of samples from bagB.

Now let’s explore how this model learns about the contents of different bags. We represent the results of learning in terms of the posterior predictive distribution for each bag: a single hypothetical draw from the bag. We will also draw a sample from the posterior predictive distribution on a new bag, for which we have had no observations.

var colors = ['black', 'blue', 'green', 'orange', 'red'];

var observedData = [

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'black'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'red'},

{bag: 'bag3', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag3', draw: 'orange'}

]

var predictives = Infer({method: 'MCMC', samples: 20000}, function(){

var makeBag = mem(function(bag){

var colorProbs = dirichlet(ones([colors.length, 1]))

return Categorical({vs: colors, ps: colorProbs})

})

var obsFn = function(datum){

observe(makeBag(datum.bag), datum.draw)

}

mapData({data: observedData}, obsFn)

return {bag1: sample(makeBag('bag1')),

bag2: sample(makeBag('bag2')),

bag3: sample(makeBag('bag3')),

bagN: sample(makeBag('bagN'))}

})

viz.marginals(predictives)

Inference suggests that the first two bags are predominantly blue, and the third is probably blue and organge. In all cases there is a fair amount of residual uncertainty about what other colors might be seen. Nothing significant is learned about bagN as it has no observations.

This generative model describes the prototypical mixture in each bag, but it does not attempt learn a common higher-order prototype. It is like learning separate prototypes for subordinate classes poodle, Dalmatian, and Labrador, without learning a prototype for the higher-level kind dog. Yet your intuition may suggest that all the bags are predominantly blue, allowing you to make stronger inferences, especially about bag3 and bagN.

Let us introduce another level of abstraction: a global prototype that provides a prior on the specific mixtures of each bag.

///fold:

var colors = ['black', 'blue', 'green', 'orange', 'red'];

var observedData = [

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'black'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'red'},

{bag: 'bag3', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag3', draw: 'orange'}

]

///

var predictives = Infer({method: 'MCMC', samples: 20000}, function(){

// we make a global prototype which is a dirichlet sample scaled to total 5.

// T.mul(d,x) multiplies the values in vector `d` by x

var phi = dirichlet(ones([colors.length, 1]))

var prototype = T.mul(phi, colors.length)

var makeBag = mem(function(bag){

var colorProbs = dirichlet(prototype)

return Categorical({vs: colors, ps: colorProbs})

})

var obsFn = function(datum){

observe(makeBag(datum.bag), datum.draw)

}

mapData({data: observedData}, obsFn)

return {bag1: sample(makeBag('bag1')),

bag2: sample(makeBag('bag2')),

bag3: sample(makeBag('bag3')),

bagN: sample(makeBag('bagN'))}

});

viz.marginals(predictives)

Compared with inferences in the previous example, this extra level of abstraction enables faster learning: more confidence in what each bag is like based on the same observed sample. This is because all of the observed samples suggest a common prototype structure, with most of its weight on blue and the rest of the weight spread uniformly among the remaining colors. In particular, we now make strong inferences for bag3 that blue is likely but orange isn’t – quite different from the earlier case without a shared global prototype.

Statisticians sometimes refer to this phenomenon of inference in hierarchical models as “sharing of statistical strength”: it is as if the sample we observe for each bag also provides a weaker indirect sample relevant to the other bags. In machine learning and cognitive science this phenomenon is often called transfer learning. Intuitively, knowing something about bags in general allows the learner to transfer knowledge gained from draws from one bag to other bags. This example is analogous to seeing several examples of different subtypes of dogs and learning what features are in common to the more abstract basic-level dog prototype, independent of the more idiosyncratic features of particular dog subtypes.

Learning about shared structure at a higher level of abstraction also supports inferences about new bags without observing any examples from that bag: a hypothetical new bag could produce any color, but is likely to have more blue marbles than any other color (see the bagN result above!). We can imagine hypothetical, previously unseen, new subtypes of dogs that share the basic features of dogs with more familiar kinds but may differ in some idiosyncratic ways.

The Blessing of Abstraction

Now let’s investigate the relative learning speeds at different levels of abstraction. Suppose that we have a number of bags that all have identical prototypes: they mix red and blue in proportion 2:1. But the learner doesn’t know this. She observes only one ball from each of N bags. What can she learn about an individual bag versus the population as a whole as the number of bags changes? We plot learning curves: the mean squared error (MSE) of the prototype from the true prototype for the specific level (the first bag) and the general level (global prototype) as a function of the number of observed data points. We normalize by the MSE of the first observation (from the first bag), to focus on the effects of diverse data. (Note that these MSE quantities are directly comparable because they are each derived from a Dirichlet distribution of the same size – this is often not the case in hierarchical models.)

var colors = ['red', 'blue'];

var posterior = function(observedData) {

return Infer({method: 'MCMC', samples: 50000}, function() {

var phi = dirichlet(ones([colors.length, 1]))

var prototype = T.mul(phi, colors.length)

var bagProbs = mem(function(bag){

return dirichlet(prototype)

})

var makeBag = mem(function(bag){

var colorProbs = bagProbs(bag)

return Categorical({vs: colors, ps: colorProbs})

})

var obsFn = function(datum){

observe(makeBag(datum.bag), datum.draw)

}

mapData({data: observedData}, obsFn)

return {bag1: T.get(bagProbs('bag1'),0),

global: T.get(phi,0)}

})

}

// data include a single sample from each bag.

var data = [{bag:'bag1', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag2', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag3', draw:'blue'},

{bag:'bag4', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag5', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag6', draw:'blue'},

{bag:'bag7', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag8', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag9', draw:'blue'},

{bag:'bag10', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag11', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag12', draw:'blue'}]

//compute the posteriors for different amounts of observations

var numObs = [1,3,6,9, 12]

var posteriors = map(function(N){posterior(data.slice(0,N))}, numObs)

//Helper fn to compute the mean-squared error of a posterior

var meanDev = function(dist, param, truth) {

return expectation(dist, function(val) {return Math.pow(truth - val[param], 2)})

}

//MSE curves normalized by the one-observations error

var initialSpec = meanDev(posteriors[0], 'bag1', 0.66)

var specErrors = map(function(d){meanDev(d,'bag1',0.66)/initialSpec}, posteriors)

var initialGlob = meanDev(posteriors[0], 'global', 0.66)

var globErrors = map(function(d){meanDev(d,'global',0.66)/initialGlob}, posteriors)

//now we generate learning curves!

print("bag1 error")

viz.line(numObs, specErrors)

print("global error")

viz.line(numObs, globErrors)

What we see is that learning is faster at the general level than the specific level—that is that the error in the estimated prototype drops faster in the general than the specific plots. We also see that there is continued learning at the specific level, even though we see no additional samples from the first bag after the first; this is because the evolving knowledge at the general level further constrains the inferences at the specific level. Going back to our familiar categorization example, this suggests that a child could be quite confident in the prototype of “dog” while having little idea of the prototype for any specific kind of dog—learning more quickly at the abstract level than the specific level, but then using this abstract knowledge to constrain expectations about specific dogs.

This dynamic depends crucially on the fact that we get very diverse evidence: let’s change the above example to observe the same N examples, but coming from a single bag (instead of N bags).

var data = [{bag:'bag1', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag1', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag1', draw:'blue'},

{bag:'bag1', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag1', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag1', draw:'blue'},

{bag:'bag1', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag1', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag1', draw:'blue'},

{bag:'bag1', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag1', draw:'red'}, {bag:'bag1', draw:'blue'}]

///fold:

var colors = ['red', 'blue'];

var posterior = function(observedData) {

return Infer({method: 'MCMC', samples: 50000}, function() {

var phi = dirichlet(ones([colors.length, 1]))

var prototype = T.mul(phi, colors.length)

var bagProbs = mem(function(bag){

return dirichlet(prototype)

})

var obsFn = function(datum){

observe(Categorical({vs: colors, ps: bagProbs(datum.bag)}), datum.draw)

}

mapData({data: observedData}, obsFn)

return {bag1: T.get(bagProbs('bag1'),0),

global: T.get(phi,0)}

})

}

//compute the posteriors for different amounts of observations

var numObs = [1,3,6,9, 12]

var posteriors = map(function(N){posterior(data.slice(0,N))}, numObs)

//Helper fn to compute the mean-squared error of a posterior

var meanDev = function(dist, param, truth) {

return expectation(dist, function(val) {return Math.pow(truth - val[param], 2)})

}

//MSE curves normalized by the one-observation error

var initialSpec = meanDev(posteriors[0], 'bag1', 0.66)

var specErrors = map(function(d){meanDev(d,'bag1',0.66)/initialSpec}, posteriors)

var initialGlob = meanDev(posteriors[0], 'global', 0.66)

var globErrors = map(function(d){meanDev(d,'global',0.66)/initialGlob}, posteriors)

///

//now we generate learning curves!

print("bag1 error")

viz.line(numObs, specErrors)

print("global error")

viz.line(numObs, globErrors)

We now see that learning for this bag is quick, while global learning (and transfer) is slow.

In machine learning one often talks of the curse of dimensionality. The curse of dimensionality refers to the fact that as the number of parameters of a model increases (i.e. the dimensionality of the model increases), the size of the hypothesis space increases exponentially. This increase in the size of the hypothesis space leads to two related problems. The first is that the amount of data required to estimate model parameters (called the “sample complexity”) increases rapidly as the dimensionality of the hypothesis space increases. The second is that the amount of computational work needed to search the hypothesis space also rapidly increases. Thus, increasing model complexity by adding parameters can result in serious problems for inference.

In contrast, we have seen that adding additional levels of abstraction (and hence additional parameters) in a probabilistic model can sometimes make it possible to learn more with fewer observations. This happens because learning at the abstract level can be quicker than learning at the specific level. Because this ameliorates the curse of dimensionality, we refer to these effects as the blessing of abstraction.

In general, the blessing of abstraction can be surprising because our intuitions often suggest that adding more hierarchical levels to a model increases the model’s complexity. More complex models should make learning harder, rather than easier. On the other hand, it has long been understood in cognitive science that learning is made easier by the addition of constraints on possible hypothesis. For instance, proponents of universal grammar have long argued for a highly constrained linguistic system on the basis of learnability. Hierarchical Bayesian models can be seen as a way of introducing soft, probabilistic constraints on hypotheses that allow for the transfer of knowledge between different kinds of observations.

Learning Overhypotheses: Abstraction at the Superordinate Level

Hierarchical models also allow us to capture a more abstract and even more important “learning to learn” phenomenon, sometimes called learning overhypotheses. Consider how a child learns about living creatures (an example we adapt from the psychologists Liz Shipley and Rob Goldstone). We learn about specific kinds of animals – dogs, cats, horses, and more exotic creatures like elephants, ants, spiders, sparrows, eagles, dolphins, goldfish, snakes, worms, centipedes – from examples of each kind. These examples tell us what each kind is like: Dogs bark, have four legs, a tail. Cats meow, have four legs and a tail. Horses neigh, have four legs and a tail. Ants make no sound, have six legs, no tail. Robins and eagles both have two legs, wings, and a tail; robins sing while eagles cry. Dolphins have fins, a tail, and no legs; likewise for goldfish. Centipedes have a hundred legs, no tail and make no sound. And so on. Each of these generalizations or prototypes may be inferred from seeing several examples of the species.

But we also learn about what kinds of creatures are like in general. It seems that certain kinds of properties of animals are characteristic of a particular kind: either every individual of a kind has this property, or none of them have it. Characteristic properties include number of legs, having a tail or not, and making some kind of sound. If one individual in a species has four legs, or six or two or eight or a hundred legs, essentially all individuals in that species have that same number of legs (barring injury, birth defect or some other catastrophe). Other kinds of properties don’t pattern in such a characteristic way. Consider external color. Some kinds of animals are homogeneous in coloration, such as dolphins, elephants, sparrows. Others are quite heterogeneous in coloration: dogs, cats, goldfish, snakes. Still others are intermediate, with one or a few typical color patterns: horses, ants, eagles, worms.

This abstract knowledge about what animal kinds are like can be extremely useful in learning about new kinds of animals. Just one example of a new kind may suffice to infer the prototype or characteristic features of that kind: seeing a spider for the first time, and observing that it has eight legs, no tail and makes no sound, it is a good bet that other spiders will also have eight legs, no tail and make no sound. The specific coloration of the spider, however, is not necessarily going to generalize to other spiders. Although a basic statistics class might tell you that only by seeing many instances of a kind can we learn with confidence what features are constant or variable across that kind, both intuitively and empirically in children’s cognitive development it seems that this “one-shot learning” is more the norm. How can this work? Hierarchical models show us how to formalize the abstract knowledge that enables one-shot learning, and the means by which that abstract knowledge is itself acquired [@Kemp2007].

We can study a simple version of this phenomenon by modifying our bags of marbles example, articulating more structure to the hierarchical model as follows. We now have two higher-level parameters: phi describes the expected proportions of marble colors across bags of marbles, while alpha, a real number, describes the strength of the learned prior – how strongly we expect any newly encountered bag to conform to the distribution for the population prototype phi. For instance, suppose that we observe that bag1 consists of all blue marbles, bag2 consists of all green marbles, bag3 all red, and so on. This doesn’t tell us to expect a particular color in future bags, but it does suggest that bags are very regular—that all bags consist of marbles of only one color.

var colors = ['black', 'blue', 'green', 'orange', 'red'];

var observedData = [

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'}, {bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'}, {bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'}, {bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'}, {bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'}, {bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'}, {bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'}, {bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'}, {bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'},

{bag: 'bag3', draw: 'red'}, {bag: 'bag3', draw: 'red'}, {bag: 'bag3', draw: 'red'},

{bag: 'bag3', draw: 'red'}, {bag: 'bag3', draw: 'red'}, {bag: 'bag3', draw: 'red'},

{bag: 'bag4', draw: 'orange'}]

var predictives = Infer({method: 'MCMC', samples: 30000}, function(){

// the global prototype mixture:

var phi = dirichlet(ones([colors.length, 1]))

// regularity parameters: how strongly we expect the global prototype to project

// (ie. determine the local prototypes):

var alpha = gamma(2,2)

var prototype = T.mul(phi, alpha)

var makeBag = mem(function(bag){

var colorProbs = dirichlet(prototype)

return Categorical({vs: colors, ps: colorProbs})

})

var obsFn = function(datum){

observe(makeBag(datum.bag), datum.draw)

}

mapData({data: observedData}, obsFn)

return {bag1: sample(makeBag('bag1')), bag2: sample(makeBag('bag2')),

bag3: sample(makeBag('bag3')), bag4: sample(makeBag('bag4')),

bagN: sample(makeBag('bagN')),

alpha: alpha}

})

viz.marginals(predictives)

Consider the fourth bag, for which only one marble has been observed (orange): we see a very strong posterior predictive distribution focused on orange – a “one-shot” generalization. This posterior is much stronger than the single observation for that bag can justify on its own. Instead, it reflects the learned overhypothesis that bags tend to be uniform in color.

To see that this is real one-shot learning, contrast with the predictive distribution for a new bag with no observations: bagN gives a mostly flat distribution. Little has been learned in the hierarchical model about the specific colors represented in the overall population; rather we have learned the abstract property that bags of marbles tend to be uniform in color. Hence, a single observation from a new bag is enough to make strong predictions about that bag even though little could be said prior to seeing the first observation.

We have also generated the posterior distribution on alpha, representing how strongly the prototype distribution captured in phi, constrains each individual bag – how much each individual bag is expected to look like the prototype of the population. You should see that the inferred values of alpha are typically significantly less than 1. This means roughly that the learned prototype in phi should exert less influence on prototype estimation for a new bag than a single observation. Hence the first observation we make for a new bag mostly determines a strong inference about what that bag is like.

Now we change the observedData :

var observedData = [

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'}, {bag: 'bag1', draw: 'red'}, {bag: 'bag1', draw: 'green'},

{bag: 'bag1', draw: 'black'}, {bag: 'bag1', draw: 'red'}, {bag: 'bag1', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'}, {bag: 'bag2', draw: 'red'}, {bag: 'bag2', draw: 'black'},

{bag: 'bag2', draw: 'black'}, {bag: 'bag2', draw: 'blue'}, {bag: 'bag2', draw: 'green'},

{bag: 'bag3', draw: 'red'}, {bag: 'bag3', draw: 'green'}, {bag: 'bag3', draw: 'blue'},

{bag: 'bag3', draw: 'blue'}, {bag: 'bag3', draw: 'black'}, {bag: 'bag3', draw: 'green'},

{bag: 'bag4', draw: 'orange'}]

///fold:

var colors = ['black', 'blue', 'green', 'orange', 'red'];

var predictives = Infer({method: 'MCMC', samples: 30000}, function(){

// the global prototype mixture:

var phi = dirichlet(ones([colors.length, 1]))

// regularity parameters: how strongly we expect the global prototype to project

// (ie. determine the local prototypes):

var alpha = gamma(2,2)

var prototype = T.mul(phi, alpha)

var makeBag = mem(function(bag){

var colorProbs = dirichlet(prototype)

return Categorical({vs: colors, ps: colorProbs})

})

var obsFn = function(datum){

observe(makeBag(datum.bag), datum.draw)

}

mapData({data: observedData}, obsFn)

return {bag1: sample(makeBag('bag1')), bag2: sample(makeBag('bag2')),

bag3: sample(makeBag('bag3')), bag4: sample(makeBag('bag4')),

bagN: sample(makeBag('bagN')),

alpha: alpha}

})

///

viz.marginals(predictives)

Intuitively, the observations for bags one, two and three should now suggest a very different overhypothesis: that marble color, instead of being homogeneous within bags but variable across bags, is instead variable within bags to about the same degree that it varies in the population as a whole. We can see this inference represented via two coupled effects. First, the inferred value of alpha is now significantly greater than 1, asserting that the population distribution as a whole, phi, now exerts a strong constraint on what any individual bag looks like. Second, for a new 'bag4' which has been observed only once, with a single orange marble, that draw is now no longer very influential on the color distribution we expect to see from that bag; the broad distribution in phi exerts a much stronger influence than the single observation.

Example: The Shape Bias

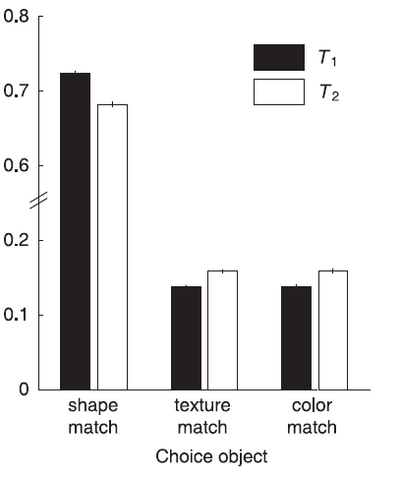

One well studied overhypothesis in cognitive development is the ‘shape bias’: the inductive bias which develops by 24 months and which is the preference to generalize a novel label for some object to other objects of the same shape, rather than say the same color or texture. Studies by Smith and colleagues [-@Smith2002] have shown that this bias can be learned with very little data. They trained 17 month old children, over eight weeks, on four pairs of novel objects where the objects in each pair had the same shape but differed in color and texture and were consistently given the same novel name. First order generalization was tested by showing children an object from one of the four trained categories and asking them to choose another such object from three choice objects that matched the shown object in exactly one feature. Children preferred the shape match. Second order generalization was also tested by showing children an object from a novel category and again children preferred the choice object which matched in shape. Smith and colleagues further found an increase in real-world vocabulary as a result of this training such that children who had been trained began to use more object names. Children had thus presumably learned something like ‘shape is homogeneous within object categories’ and were able to apply this inductive bias to word learning outside the lab.

We now consider a model of learning the shape bias which uses the compound Dirichlet-Discrete model that we have been discussing in the context of bags of marbles. This model for the shape bias is from [@Kemp2007]. Rather than bags of marbles we now have object categories and rather than observing marbles we now observe the features of an object (e.g. its shape, color, and texture) drawn from one of the object categories. Suppose that a feature from each dimension of an object is generated independently of the other dimensions and there are separate values of alpha and phi for each dimension. Importantly, one needs to allow for more values along each dimension than appear in the training data so as to be able to generalize to novel shapes, colors, etc. To test the model we can feed it training data to allow it to learn the values for the alphas and phis corresponding to each dimension. We can then give it a single instance of some new category and then ask what the probability is that the various choice objects also come from the same new category. The WebPPL code below shows a model for the shape bias, conditioned on the same training data used in the Smith et al experiment. We can then ask both for draws from some category which we’ve seen before, and from some new category which we’ve seen a single instance of. One small difference from the previous models we’ve seen for the example case is that the alpha hyperparameter is now drawn from an exponential distribution with inverse mean 1, rather than a Gamma distribution. This is simply for consistency with the model given in the Kemp et al (2007) paper.

var attributes = ['shape', 'color', 'texture', 'size'];

var values = {shape: _.range(11), color: _.range(11), texture: _.range(11), size: _.range(11)};

var observedData = [{cat: 'cat1', shape: 1, color: 1, texture: 1, size: 1},

{cat: 'cat1', shape: 1, color: 2, texture: 2, size: 2},

{cat: 'cat2', shape: 2, color: 3, texture: 3, size: 1},

{cat: 'cat2', shape: 2, color: 4, texture: 4, size: 2},

{cat: 'cat3', shape: 3, color: 5, texture: 5, size: 1},

{cat: 'cat3', shape: 3, color: 6, texture: 6, size: 2},

{cat: 'cat4', shape: 4, color: 7, texture: 7, size: 1},

{cat: 'cat4', shape: 4, color: 8, texture: 8, size: 2},

{cat: 'cat5', shape: 5, color: 9, texture: 9, size: 1}]

var categoryPosterior = Infer({method: 'MCMC', samples: 10000}, function(){

var prototype = mem(function(attr){

var phi = dirichlet(ones([values[attr].length, 1]))

var alpha = exponential(1)

return T.mul(phi,alpha)

})

var makeAttrDist = mem(function(cat, attr){

var probs = dirichlet(prototype(attr))

return Categorical({vs: values[attr], ps: probs})

})

var obsFn = function(datum){

map(function(attr){observe(makeAttrDist(datum.cat,attr), datum[attr])},

attributes)

}

mapData({data: observedData}, obsFn)

return {cat5shape: sample(makeAttrDist('cat5','shape')),

cat5color: sample(makeAttrDist('cat5','color')),

catNshape: sample(makeAttrDist('catN','shape')),

catNcolor: sample(makeAttrDist('catN','color'))}

})

viz.marginals(categoryPosterior)

The program above gives us draws from some novel category for which we’ve seen a single instance. In the experiments with children, they had to choose one of three choice objects which varied according to the dimension they matched the example object from the category. We show below model predictions (from Kemp et al (2007)) for performance on the shape bias task which show the probabilities (normalized) that the choice object belongs to the same category as the test exemplar. The model predictions reproduce the general pattern of the experimental results of Smith et al in that shape matches are preferred in both the first and second order generalization case, and more strong in the first order generalization case. The model also helps to explain the childrens’ vocabulary growth in that it shows how the shape bias can be generally learned, as seen by the differing values learned for the various alpha parameters, and so used outside the lab.

The model can be extended to learn to apply the shape bias only to the relevant ontological kinds, for example to object categories but not to substance categories. The Kemp et al (2007) paper discusses such an extension to the model which learns the hyperparameters separately for each kind and further learns what categories belong to each kind and how many kinds there are. This involves the use of a non-parametric prior, called the Chinese Restaurant Process, which will be discussed in the section on non-parametric models.

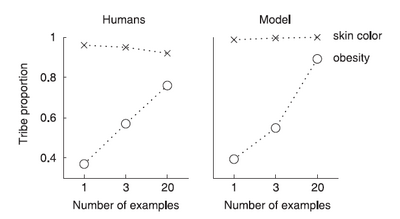

Example: Beliefs about Homogeneity and Generalization

In a 1983 paper, Nisbett and colleagues [-@Nisbett1983] examined how, and under what conditions, people made use of statistical heuristics when reasoning. One question they considered was how and when people generalized from a few instances. They showed that to what extent people generalise depends on beliefs about the homogeneity of the group that the object falls in with respect to the property they are being asked to generalize about. In one study, they asked subjects the following question:

Imagine that you are an explorer who has landed on a little known island in the Southeastern Pacific. You encounter several new animals, people, and objects. You observe the properties of your “samples” and you need to make guesses about how common these properties would be in other animals, people, or objects of the same type.

The number of encountered instances of an object were varied (one, three, or twenty instances) as well as the type and property of the objects. For example:

Suppose you encounter a native, who is a member of a tribe he calls the Barratos. He is obese. What percent of the male Barratos do you expect to be obese?

and

Suppose the Barratos man is brown in color. What percent of male Barratos do you expect to be brown (as opposed to red, yellow, black or white)?

Results for two questions of the experiment are shown below. The results accord both with the beliefs of the experimenters about how heterogeneous different groups would be, and subjects stated reasons for generalizing in the way they did for the different instances (which were coded for beliefs about how homogeneous objects are with respect to some property).

Again, we can use the compound Dirichlet-multinomial model we have been working with throughout to model this task, following Kemp et al (2007). In the context of the question about members of the Barratos tribe, replace bags of marbles with tribes and the color of marbles with skin color, or the property of being obese. Observing data such that skin color is consistent within tribes but varies between tribes will cause a low value of the alpha corresponding to skin color to be learned, and so seeing a single example from some new tribe will result in a sharply peaked predictive posterior distribution for the new tribe. Conversely, given data that obesity varies within a tribe the model will learn a higher value of the alpha corresponding to obesity and so will not generalize nearly as much from a single instance from a new tribe. Note that again it’s essential to have learning at the level of hyperparameters in order to capture this phenomenon. It is only by being able to learn appropriate values of the hyperparameters from observing a number of previous tribes that the model behaves reasonably when given a single observation from a new tribe.

Example: One-shot learning of visual categories

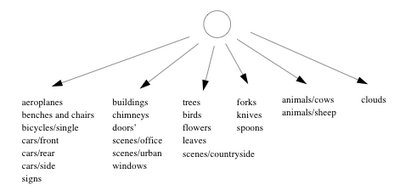

Humans are able to categorize objects (in a space with a huge number of dimensions) after seeing just one example of a new category. For example, after seeing a single wildebeest people are able to identify other wildebeest, perhaps by drawing on their knowledge of other animals. The model in Salakhutdinov et al [-@Salakhutdinov2010] uses abstract knowledge learned from other categories as a prior on the mean and covariance matrix of new categories.

Suppose, first that the model is given an assignment of objects to basic categories and basic categories to superordinate categories. Objects are represented as draws from a multivariate Gaussian and the mean and covariance of each basic category is determined by hyperparameters attached to the corresponding superordinate category. The parameters of the superordinate categories are all drawn from a common set of hyperparameters.

The model in the Salakhutdinov et al (2010) paper is not actually given the assignment of objects to categories and basic categories to superordinate categories, but rather learns this from the data by putting a non-parametric prior over the tree of object and category assignments.

Example: X-Bar Theory

(This example comes from an unpublished manuscript by O’Donnell, Goodman, and Katzir)

One of the central problems in generative linguistics has been to account for the ease and rapidity with which children are able to acquire their language from noisy, incomplete, and sparse data. One suggestion for how this can happen is that the space of possible natural languages varies parametrically. The idea is that there are a number of higher-order constraints on structure that massively reduce the complexity of the learning problem. Each constraint is the result of a parameter taking on one of a small set of values. (This is known as “principles and parameters” theory.) The child needs only see enough data to set these parameters and the details of construction-specific structure will then generalize across the rest of the constructions of their language.

One example, is the theory of headedness and X-bar phrase structure [@Chomsky1970] [@Jackendoff1981]. X-bar theory provides a hierarchical model for phrase structure. All phrases follow the same basic template:

\(XP \longrightarrow Spec \ X^\prime\) \(X^\prime \longrightarrow X \ Comp\)

Where \(X\) is a lexical (or functional) category such as \(N\) (noun), \(V\) (verb), etc. X-bar theory proposes that all phrase types have the same basic “internal geometry”; They have a head – a word of category \(X\). They also have a specifier (\(Spec\)) and a complement ($Comp$), the complement is more closely associated with the head than the specifier. The set of categories that can appear as complements and specifiers for a particular category of head is usually thought to be specified by universal grammar (but may also vary parametrically).

An important way in which languages vary is the order in which heads appear with respect to their complements (and specifiers). Within a language there tends to be a dominant order, often with exceptions for some category types. For instance, English is primarily a head-initial language. In verb phrases, for example, the direct object (complement noun phrase) of a verb appears to the right of the head. However, there are exceptional cases such as the order of (simple) adjective and nouns: adjectives appear before the noun rather than after it (although more complex complement types such as relative clauses appear after the noun).

The fact that languages show consistency in head directionality could be of great advantage to the learner; after encountering a relatively small number of phrase types and instances the learner of a consistent language can learn the dominant head direction in their language, transferring this knowledge to new phrase types. The fact that within many languages there are exceptions suggests that this generalization cannot be deterministic, however, and, furthermore means that a learning approach will have to be robust to within-language variability. Here is a highly simplified model of X-Bar structure:

///fold:

var observePhrase = function(dist, values) {

return sum(map(function(v) {return dist.score(v)}, values));

}

///

// the "grammar": a set of phrase categories, and an associating of the complement to each head category:

var categories = ['D', 'N', 'T', 'V', 'A', 'Adv']

var headToComp = function(head) {

return (head == 'D' ? 'N' :

head == 'T' ? 'V' :

head == 'N' ? 'A' :

head == 'V' ? 'Adv' :

head == 'A' ? 'none' :

head == 'Adv' ?'none' :

'error');

}

var makePhraseDist = function(headToPhraseDirs) {

return Infer({method: 'enumerate'}, function(){

var head = uniformDraw(categories);

if(headToComp(head) == 'none') {

return [head]

} else {

// On which side will the head go?

return flip(headToPhraseDirs[head]) ? [headToComp(head), head] : [head, headToComp(head)];

}

})

}

var data = [['D', 'N']];

var results = Infer({method: 'MCMC', samples: 20000}, function() {

var languageDir = beta(1,1);

var headToPhraseDirs = _.zipObject(categories, map(function() {

return T.get(dirichlet(Vector([languageDir, 1 - languageDir])), 1)

}, categories))

var phraseDist = makePhraseDist(headToPhraseDirs);

factor(observePhrase(phraseDist, data))

return flip(headToPhraseDirs['N']) ? 'N second' : 'N first';

})

viz.auto(results)

First, try increasing the number of copies of ['D', 'N'] observed. What happens? Now, try changing the data to [['D', 'N'], ['T', 'V'], ['V', 'Adv']]. What happens if you condition on additional instance of ['V', 'Adv']? How about ['Adv', 'V']?

What we see in this example is a simple probabilistic model capturing a version of the “principles and parameters” theory. Because it is probabilistic, systematic inferences will be drawn despite exceptional sentences or even phrase types. More importantly, due to the blessing of abstraction, the overall headedness of the language can be inferred from very little data—before the learner is very confident in the headedness of individual phrase types.

Thoughts on Hierarchical Models

We have just seen several examples of hierarchical Bayesian models: generative models in which there are several levels of latent random choices that affect the observed data. In particular a hierarchical model is usually one in which there is a branching structure in the dependence diagram, such that the “deepest” choices affect all the data, but they only do so through a set of more shallow choices which each affect some of the data, and so on.

Hierarchical model structures give rise to a number of important learning phenomena: transfer learning (or learning-to-learn), the blessing of abstraction, and learning curves with fairly abrupt transitions. This makes them important for understanding human learning, as well as useful for creating artificial intelligence that makes the best use of available data.

Hierarchical Abstraction versus Lambda Abstraction

We have spoken of the earlier choices in a hierarchical model as being more “abstract.” In computer science the function operator is often called lambda abstraction. Are these two uses of “abstract” related?

There is a third notion of abstraction in a generative model which may explain the relation between these two: if we have a designated set of observations (or more generally a function that we think of as generating “perceptual” data) we can say that a random choice is abstract if it is far from the data. More specifically the degree of abstraction of an expression in a probabilistic program is the number of immediate causal dependencies (edges) from the expression to the designated observation expression (note that this is a partial, not strict, ordering on the random choices).

In a hierarchically structured model the deeper random choices are more abstract in this sense of causal distance from the data. More subtly, when a procedure is created with function the expressions inside this procedure will tend to be more causally distant from the data (since the procedure must be applied before these expressions can be used), and hence greater depth of lambda abstraction will tend to lead to greater abstraction in the causal distance sense.

Test your knowledge: Exercises

Reading & Discussion: Readings

Next chapter: 12. Occam's Razor